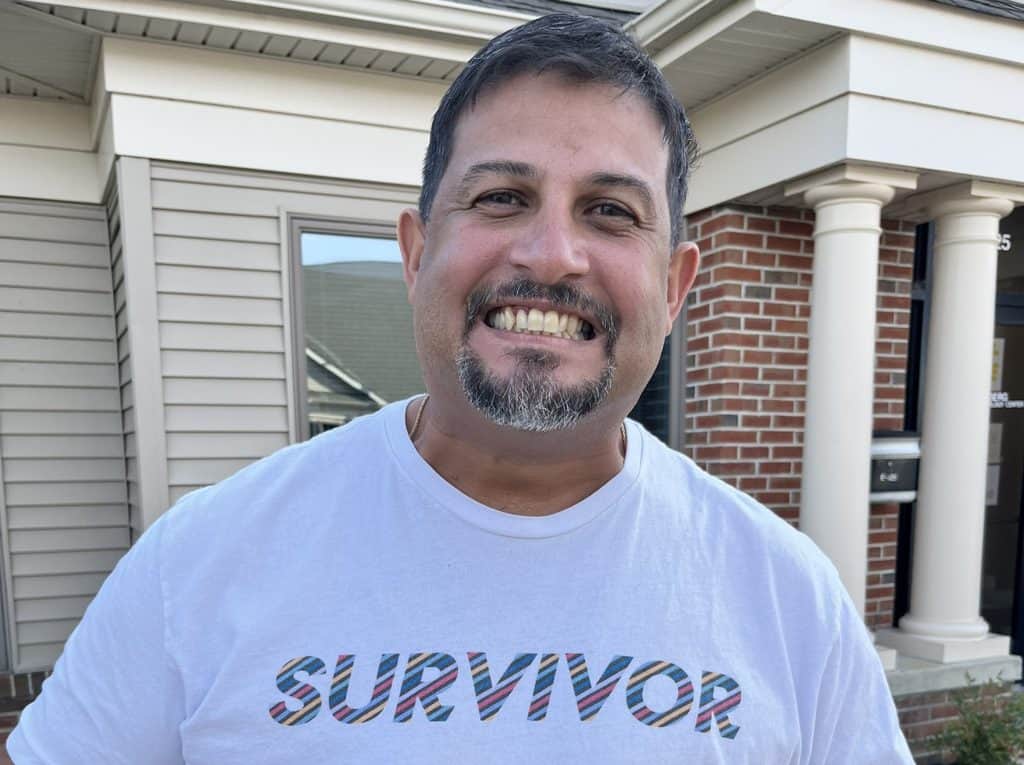

Juan Namnun talks about his breast cancer in sports metaphors. Just before his double mastectomy last month, the 44-year-old father of three boys tweeted: “My fight with cancer had a tough preseason. Today is my opening day. Surgery.”

Sports lingo is his comfort zone. As head coach of the Frankford High School baseball team, Namnun brought home the coveted city championship in 2017, besting more than 80 teams. During his 14 years at the helm, his team won seven Public League crowns — an all-time record in Philadelphia history. Namnun, who teaches health and physical education at Frankford, also coached football and bowling, and has worked for the Phillies as an interpreter for Spanish-speaking players, a youth camp director, and helped with in Clearwater. Now he has a new mission.

While recovering from surgery earlier this month, Namnun turned on ABC’s Good Morning America to watch anchor Robin Roberts, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2007, interview two doctors for the show’s “Thriving in Pink” series. “They’re all in pink. And the set is all in pink,” Namnun said.

He grabbed his cell phone. “Hi Robin. Thank you for this great piece. If possible, please include men,” he tweeted at her. “We need to break the stigma that it’s only a woman’s issue. Too many men ignore lumps until it’s too late.” To his amazement, Roberts acknowledged his tweet on-air, he said.

Cancer treatment is often scary and even embarrassing, but for Namnun, the journey was especially isolating. There were so many awkward moments, from the receptionist who looked around for a female patient and asked “What’s her name?” when he checked in for an appointment, to the medical tech who apologized when an electrode sticker got tangled in his chest hair. “You’re my first man,” nurses and doctors told him all along the way. “It’s like if you take your car to the mechanic and you hear: ‘Hey, this is my first time working on this one. I can’t wait.’ It’s not comforting,” he said.

When Namnun got referred to Virtua Cancer Center for Women after his diagnosis, he donned the pink gown he was given. The surgeon said she’d need to remove his right breast; the left was his decision. “Some women,” she said, before correcting herself, “some people do it to be careful down the road,” Namnun recalled. The reason most men associate breast cancer with women is not just societal. It’s statistical.

Namnun initially ignored the stone-like lump when he felt it on his right breast in June. That’s typical among the men seen at South Jersey Radiology, where Namnun had his first mammogram.

Namnun found there was no playbook specific to his needs as a man. He agonized for days on whether to remove both breasts, talking it over with his wife as they walked Abbey, their shih tzu. Pain was not his only consideration. “I’m going to look different. It’s a sad reality. I like the outdoors — if I take my shirt off to go swimming, I’m going to look a certain way,” Namnun said.

Ultimately, he decided to remove both breasts. When he awoke after the outpatient procedure, the surgeon told him she found a second, cancerous tumor hidden behind the first one. The discovery, “a massive red flag,” meant a double mastectomy was inevitable.

He’s still in a lot of physical pain. And he can’t bear to look at his chest in the mirror. “Physically, you’re used to an appearance. I played sports most of my life. I had a little bit of a muscular look, if you will, slightly,” he said somewhat sheepishly. “That’s gone now. There’s a flatness here. They took the nipples,” he said.

His surgeon told him she’s had patients who don’t look at themselves for six months. A female friend who had breast cancer tried to reassure him. “You’re going to feel like a different person, but you’re going to be the same. You have to trust that,” he said she told him.

Breast cancer was the last thing on Namnun’s mind one morning in late June, when he and his wife, Lena, also a Frankford High teacher, were “bobbing around” in the swimming pool of their backyard in Delran, Burlington County. A leaf got stuck to Namnun’s right breast. When he brushed it away, he felt a lump about the size of a quarter. He said nothing to his wife. “It’s a bump. I probably hit myself,” he thought. “I’m an active guy, maybe I walked into the door? It’s no big deal. What can it be, really?”

Breast cancer can be symptomless in its early stages, detectable only with screening tests like mammograms. But as it progresses, the signs are similar in all genders: a new lump in the breast or armpit, swelling in part of the breast, skin irritation or dimpling, and discharge or pain in the nipple area.

A few weeks later, Lena Namnun leaned against him and felt it. She insisted he go to the doctor. The doctor thought it was “a fluid-filled cyst,” probably nothing, but just in case, he ordered an ultrasound and a mammogram. “I immediately went, ‘What? What?’ I was quite confused and slightly nervous.”

The mammogram itself was uncomfortable, psychologically and physically. “They had trouble getting me in the machine because I certainly don’t have the average amount of,” Namnun suddenly paused, searching for a diplomatic word, “mass. It was like squeezing paper.” The radiologist told Namnun he needed a biopsy of the lump. He also ordered a screen of his left, unaffected breast.

The biopsy procedure was “almost traumatizing.” He never imagined that doctors numb the breast, “core” into the skin, and leave a tiny piece of titanium to mark where they removed breast tissue. “I don’t wish that on anybody,” he said. It felt “invasive,” though he recognized that it’s routine. “If you grabbed 100 men and asked, ‘Do you know the process for breast cancer, like what happens?’, ninety percent would have no clue.”

Namnun said he had two types of breast cancer: papillary carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS, considered the earliest form. Further testing revealed no genetic predisposition. The surgeon told him she rarely sees this, and not ever in a man, he recalled.

He’s now on oral chemotherapy. The doctor isn’t sure how the drug will affect Namnun, such as whether he’ll lose his hair, because all the data and studies on efficacy and side effects pertain to women.

“He had a hot flash yesterday — poetic justice,” his wife teased during an interview Wednesday at the couple’s home.

Namnun, who is on medical leave, said he hopes to return to teaching and to his job as Frankford’s head baseball coach soon. His team misses him. Both Frankford and Delran High School, where his two youngest sons play on the football team, made T-shirts with a pink and blue ribbon in his honor.

The day after surgery, his wife gently removed his bandages so he could wash. He caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror. “I had a complete breakdown. I just sobbed. I felt bad that she had to see me this way because I love her very much.” Casting a nervous glance at his wife, whom he met when they were freshmen at Frankford High, he admits he worries she won’t find him as attractive. “First of all, I look at your eyes and your butt. I don’t care what’s in between,” Lena, 45, said with a slight laugh. Then she got serious. “If the shoe were on the other foot and they had to take mine, would you look at me differently? Would you think I’m ugly? No. I’m not going anywhere,” she said. She’s clearly said this before, but he needs the repetition.

“I guess sometimes you need to hear something like that,” he said. “I couldn’t imagine being a man alone throughout this process.”

Article courtesy Philadelphia Inquirer